Vietnam in Venice

By Kwok Kian Chow

The Venice Biennale is where art and nations meet to shout out how they alwaysneed, but sometimes dislike, each other. For the first exhibition of Vietnamese artists presented in the Venice Biennale as a group, instead of the usual route of accessing Venice via a national pavilion, they appear to have found an excellent platform the name of which cannot be more fitting – Personal Structures.

For Ho Chi Minh City-based Nguyen Trung (b. 1940), Do Hoang Tuong (b. 1960), Nguyen Son (b. 1974); and Hanoi-based Tulip Duong (b. 1959), and Ly Tran Quynh Giang (b. 1978), their works presented are personal forms - as individualistic expressions, and as testimony to their personal trajectories. Yet their art practice paths crossed, within the common context, image and stylistic conventions, and art education (except for Duong, a mathematician turned artist) of the Vietnamese art world. Trung has been a leading figure first in the Southern Vietnamese art scene, and nationally after Reunification (1976).

Trung’s personal fondness for the art of Soulages, Tàpies and Zao Wou Ki is heard echoed in younger artists such as Tuong. Trung singled out writings in philosophy and art which inspired him most -- Michel Ragon, Henri Bergson, Tagore and 17 th century Shitao. The six works (Trung shows two works) in Venice represent important moments of ‘personal structures’ for the artists. The works also serve as a ‘Vietnam Pavilion’, but within a zone not of national representation, but of concrete personal moments, and yet not without abundant clues into the world of Vietnamese art. If art and nation had to coincide, the Vietnamese group within Personal Structures offers a refreshing perspective.

As an exhibition platform, Personal Structures eliminates the linear and ideological notion of history and art development. In so doing, it becomes an open forum for artists and art works to interface. The Venice Biennale context, on the other hand, is still one that is predicated on national representation/pavilion, signaling the reality that only one extraordinary international exposition of art will perpetually be that pedestal where nations would parade. Appended to Personal Structures, the Vietnam artist group is lightly national, and the works and contexts quickly point the visitors to the diversity within Vietnamese contemporary art practices.

The full title of Personal Structures is Personal Structures: Time, Space, Existence, the explication on which was developed in the essay “Time. Space. Existence” by Peter Lodermeyer (2009). Time is also a central concern for the Vietnamese artists. For Trung, time relays through distances, and the “images from the past”, having taken a great length of time in crystallization, culminated in his abstract works. Lodermeyer relates Heidegger’s “time is Dasein… Dasein always is in the manner of its possible temporal being… Dasein is its past, it is its possibility in running ahead to this past.” These lines may also be invoked to explain Trung’s painting practices. Indeed, as expounded by Lodermeyer, time as duration is understood as a temporality that is subjective. The title of Trung’s MA 1 (2015, acrylic on canvas) refers to the images that look like the alphabets M and A, while a variety of brush and gestural strokes, and blocks, lines and drips point to a temporality of being. To locate Trung’s MA 1 in the broader context of his oeuvre, time as a theme is key. In his earlier figurative works, the present (the “instantaneous” as the artist has it) is anchored in the figurative, while the painterly and compositional, or formal elements, pointed towards his life-long project of abstract works, understood in their gestation over longue durée.

There is also time as in art history. The cross references of the artists in this exhibition points to the prominent role of Trung as a mentor, to a geography much larger than Ho Chi Minh City. Trung was a founding member of the Young Artists Association, a vanguard art group in Saigon active from 1966 up to the Reunification. In The Light (2016, lamp, stretched canvas, acrylic), Trung does not purposefully looks for objects for incorporation into his works, but rather these objects are there and have been under consideration, so to speak, for the longest time as the artist traverses through a temporality of time but materially and geographically narrowed within the discipline of the studio and vicinity. Sculptural works form a continuum to the paintings, “when painting is not enough” as Trung has it, framed within the same temporality of being. A different concern for time is seen in Son’s Nostalgia (2017, epoxy, acrylic, ink, aluminum and steel). The six objects are one work, but each is also a stand-alone, like duration and moments. “The invisible hand represents time”. The large metal spoon was an architype for scoop, used all over Northern Vietnam in every single meal. The invisible hand and the metal spoon are universal, the omnipresence of time as a frame within which human actions and emotions unfolded.

When evoked through memories and images, time has a fluid physical presence in a sequence that is both about human sentiments as well as actual events that occurred, as they are imprinted in memory. The six sculptural elements capture events that happened within a day of family outing during Son’s youth, chronicling anxiety, relief, parental love, and friendship. A photograph taken by the Cuban artist Vidal Hernandez during that occasion, is now digitally reconfigured for the individual sculptural elements. Episodes here are sequence within a day, and yet each moment is a standalone, triggering a certain emotion in the larger topography of temporality. This new work came after Son’s recent series montaging Duchamp’s Fountain with other icons such as a portrait of Lenin, as the artist’s reflections on historical imagery and coincidences in times, such as the same year (1917) of the first exhibition of Duchamp’s Fountain, and the formation of the Soviet Russia. The coincidence of such historical moments is significant to Vietnam given its communist background, and its art given the inspiration of avant-garde practices. The two figurative works in the exhibition, Tuong’s Black Party (2016, acrylic and oil on canvas) and Giang’s Where They Turn To (2016, carved wood) speak of human condition with psychological intensity.

Tuong enrolled in the art college in the very year of Reunification. His frequent discussions with Trung continued as he became an art teacher and an illustrator. A highly accomplished one, he continues to work in illustration while his painting appeared to take on separate trajectories. Tuong returned to figurative works in 2004 with the S/he series. The artist painted women in bodily contortions which would have been impossible in physiological term in the subsequent 12 Women series. As an anatomy lecturer, Tuong knew exactly the physiological boundaries that he wanted to subtly trespassed, so as to formulate a commentary on the status of women, a suffrage seemingly natural but physically torturous. The Black Party shows a concluding moment of a party indicated by the near empty wine glass, with a photo line-up formation group image of six suit cladding men and one naked woman. Tuong explained the image as a general mood of “unsettling” in the world. Another work painted around this time (late 2016) bears the title, The President.

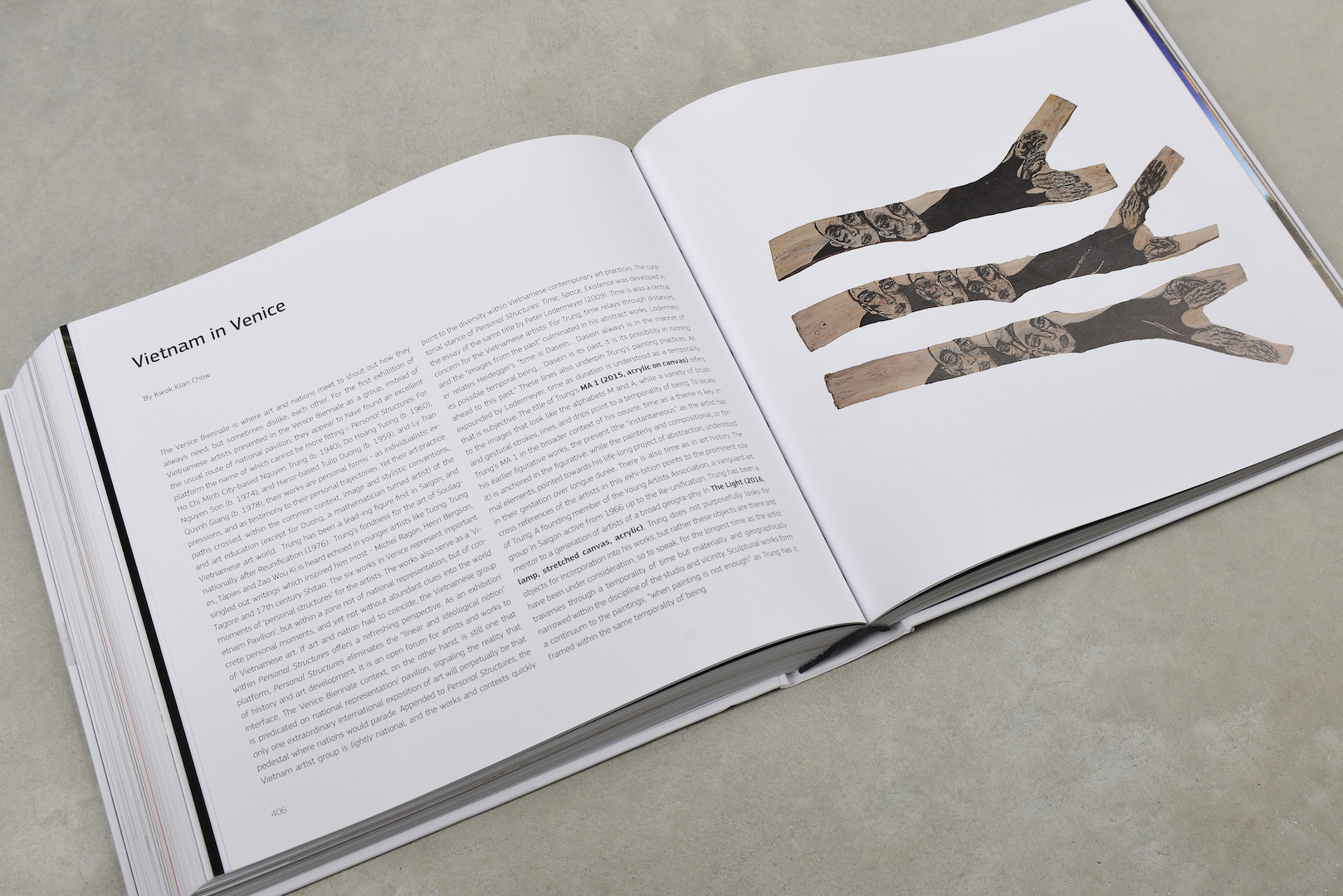

Giang’s Where They Turn To is also a work of impossible anatomy intensified by the natural form and texture of the Dunn blocks. Giang has created expressionistic works since graduation from the Hanoi Fine Arts University (2002). The works often depict existential conditions shared by humans and the natural world alike. Humans appear with trees and fishes, and “their conjoining in a work is because of their shared condition”. For the human figure, apart from the physiological features of male and female, there is no gender differentiation. Giang’s world is also one of continuous erasures of socially and culturally constructed distinctions within the greater ecology. Where They Turn To speak of struggles set within natural forms of tree trunks with arms stretched to torturous lengths as these were the directions of hope, guided by the trees. Duong’s career has the unusual combination of mathematician, educator, marketing analyst, and artist. When, however, the oeuvre of her artwork is looked at holistically, the above combination makes sense. The artist’s project is characterized by turning mathematics to artistic strategies, marketing into communication, and art into a realm of limitless possibilities. Artistic articulation to Duong is a sheer pleasure and freedom. OCDM (2016, lacquer on wood, cremones), a work comprising two panels in the cremone (door latch) series has been developed from her earlier landscape paintings capturing views beyond the window. Viewers are always invited to step outside to the world of freedom, just as they are invited to turn the cremone knob to unfasten their inhibition. Highly methodical in her art making, Duong typically gathers a large pool of materials, resources, concepts and processes, before selecting a key theme for a new series, and working through the many artworks to reinforce the theme from various angles.

The artist’s switch from mathematics and education to management came just shortly after Doi Moi (1986), with the national move towards market economy. Duong offered to teach marketing in the reconstituted University of Commerce, in gearing up the management support for the open economy. As an artist, she is now taking her multidisciplinary endeavour to inspire personal liberty. During my conversations with the five artists, each invoked at some point the term “Oriental” or “Asian”. I came to realize that there is still much to be understood about the context of Vietnam, through the six and numerous works we looked at and discussed. While there is every recognition of multiple sources of inspirations and references in the art practices of these artists, I felt that the term “Oriental” or “Asian” served as a reminder on the deeply felt cultural differences and the lived experience of Vietnam in comparison with other biographies, aesthetics and expressions in talking about art in a global context. I regard the term as a marker of a contingency of difference, as we explore more into the world of contemporary art in Vietnam. I return to the point about a national pavilion as methodology.